Introduction

Physical therapy in Asheville for Shoulder Issues

Welcome to Combined Therapy Specialties resource about shoulder dislocations.

Welcome to Combined Therapy Specialties resource about shoulder dislocations.

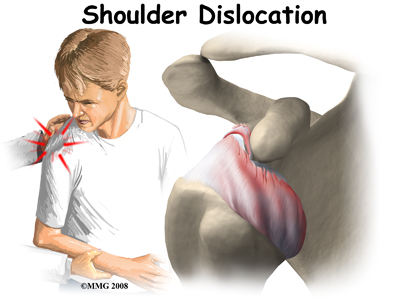

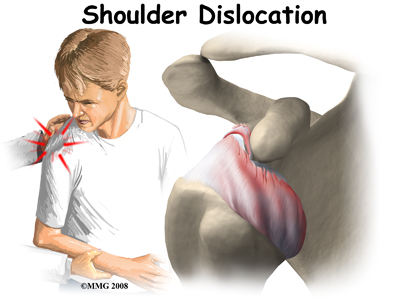

A shoulder dislocation is a painful and disabling injury of the glenohumeral joint. Most dislocations are anterior (forward) but the shoulder can also dislocate posteriorly (backwards). Inferior and posterolateral dislocations are possible but occur much less often. The specific type of dislocation is based on the position of the humeral head in relation to the glenoid (shoulder socket) at the time of the diagnosis.

This guide will help you understand:

- what parts of the shoulder are involved

- how the problem develops

- how health care professionals diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

- what Combined Therapy Specialties approach to rehabilitation is

#testimonialslist|kind:all|display:slider|orderby:type|filter_utags_names:Shoulder Pain|limit:15|heading:Hear from some of our patients who we treated for *Shoulder Pain*#

Anatomy

What parts of the body are involved?

The shoulder has a unique and complex anatomy that allows range of motion and coordination needed for reaching, lifting, throwing, and many other movements. Understanding the anatomical structures discussed will help you understand why your shoulder dislocated.

The shoulder has a unique and complex anatomy that allows range of motion and coordination needed for reaching, lifting, throwing, and many other movements. Understanding the anatomical structures discussed will help you understand why your shoulder dislocated.

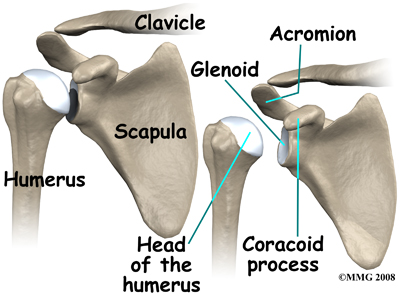

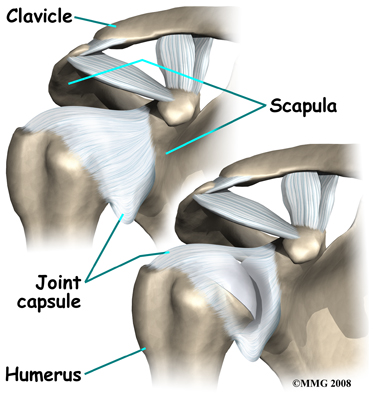

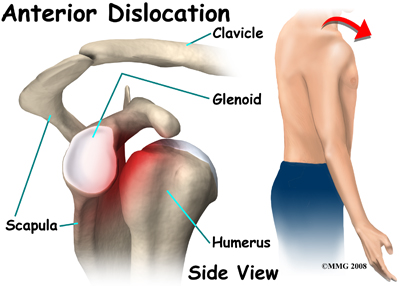

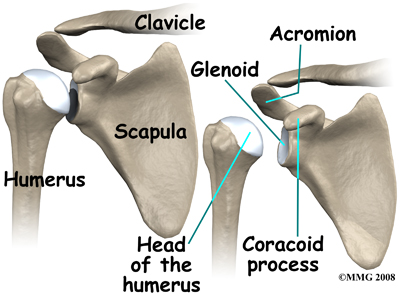

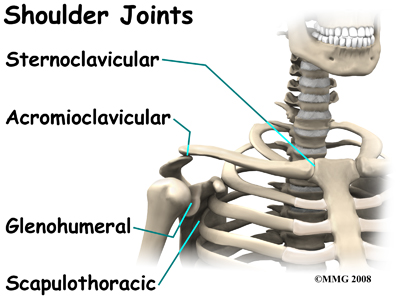

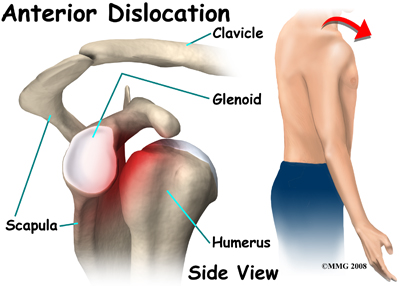

The bones of the shoulder are the humerus (the upper arm bone), the scapula (the shoulder blade), and the clavicle (the collar bone). The roof of the shoulder is formed by a part of the scapula called the acromion.

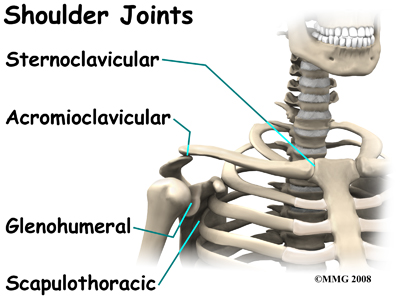

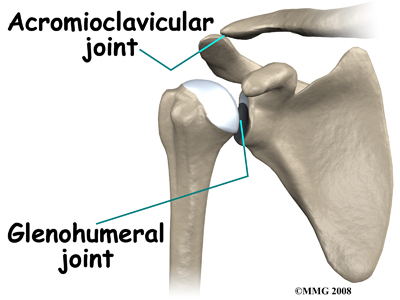

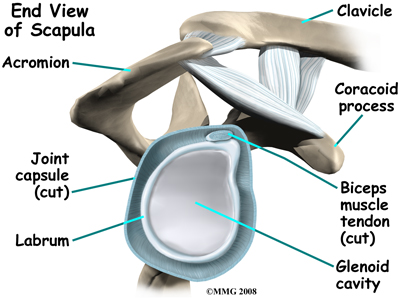

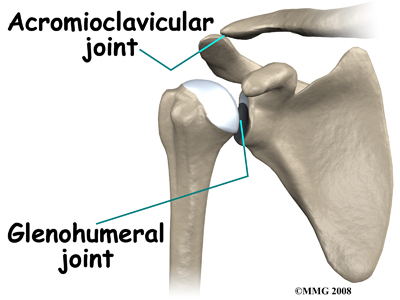

There are actually four joints that make up the shoulder. The main shoulder joint, called the glenohumeral joint, is formed where the ball of the humerus fits into a shallow socket on the scapula. This shallow socket is called the glenoid.

The acromioclavicular (AC) joint is where the clavicle meets the acromion. The sternoclavicular (SC) joint supports the connection of the arms and shoulders to the main skeleton on the front of the chest. The scapulothoracic joint is formed where the shoulder blade glides against the thorax (the rib cage). This joint is especially important because the muscles surrounding the shoulder blade work together to keep the socket lined up during shoulder movements.

Ligaments, Joint Capsule, and Labrum

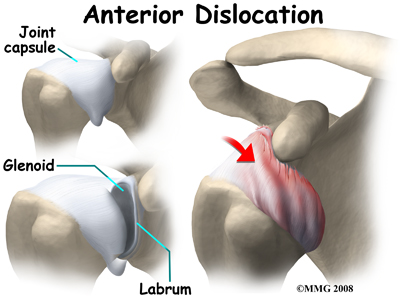

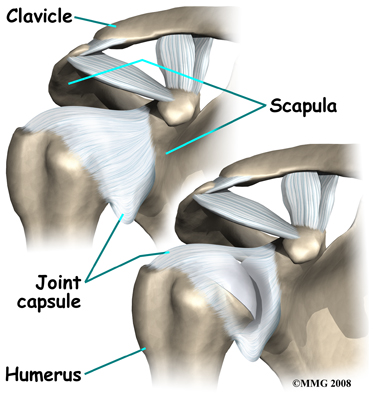

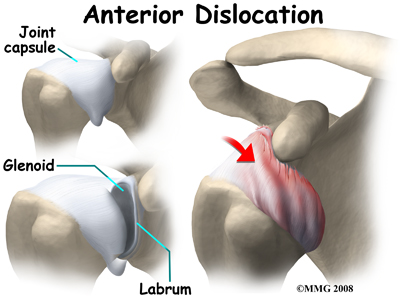

There are several important ligaments in the shoulder. Ligaments are soft tissue structures that connect bones to bones. A joint capsule is a watertight sac that surrounds a joint. In the shoulder, the joint capsule is formed by a group of ligaments that connect the humerus to the glenoid. These ligaments are the main source of stability for the shoulder; they help hold the shoulder in place and keep it from dislocating.

There are several important ligaments in the shoulder. Ligaments are soft tissue structures that connect bones to bones. A joint capsule is a watertight sac that surrounds a joint. In the shoulder, the joint capsule is formed by a group of ligaments that connect the humerus to the glenoid. These ligaments are the main source of stability for the shoulder; they help hold the shoulder in place and keep it from dislocating.

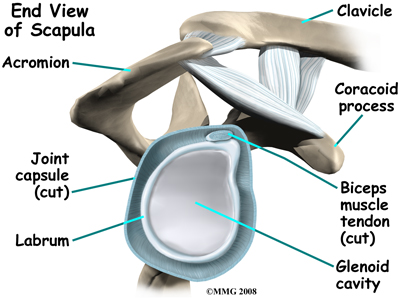

The labrum is a special cartilaginous structure inside the shoulder. It is attached almost completely around the edge of the glenoid. When viewed in cross section, the labrum is wedge-shaped. The shape and the way the labrum is attached create a deeper cup for the glenoid socket and helps to prevent dislocation by creating more stability. This is important because the glenoid socket is so flat and shallow that the ball of the humerus does not fit tightly. This anatomical shape allows great mobility of the shoulder, but unfortunately does not provide much stability, hence the reason it dislocates much easier than some other joints.

The labrum is also where the long biceps tendon from the upper arm attaches to the glenoid. Tendons attach muscles to bones. Muscles move the bones by pulling on the tendons. The biceps tendon runs from the biceps muscle, up the front of the upper arm, to the glenoid. At the very top of the glenoid, the biceps tendon attaches to the bone and actually becomes part of the labrum. This connection can be a source of problems when the biceps tendon is damaged and pulls away from its attachment to the glenoid.

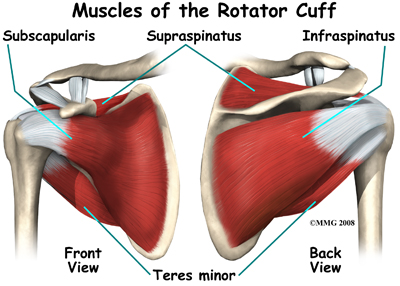

The Rotator Cuff

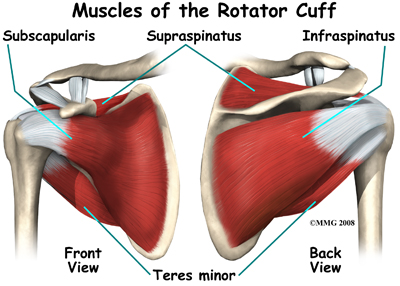

The tendons of the rotator cuff are the next layer in the shoulder joint. Four rotator cuff tendons connect the deepest layer of muscles to the humerus. This group of muscles attaches from the shoulder blade to the humerus. These muscles help raise the arm from the side and rotate the shoulder in the many directions. They are extremely important muscles to the shoulder and are involved in many day-to-day activities. The rotator cuff muscles and tendons are extremely important in assisting glenohumeral joint stability because they help hold the humeral head in the shallow glenoid socket.

The tendons of the rotator cuff are the next layer in the shoulder joint. Four rotator cuff tendons connect the deepest layer of muscles to the humerus. This group of muscles attaches from the shoulder blade to the humerus. These muscles help raise the arm from the side and rotate the shoulder in the many directions. They are extremely important muscles to the shoulder and are involved in many day-to-day activities. The rotator cuff muscles and tendons are extremely important in assisting glenohumeral joint stability because they help hold the humeral head in the shallow glenoid socket.

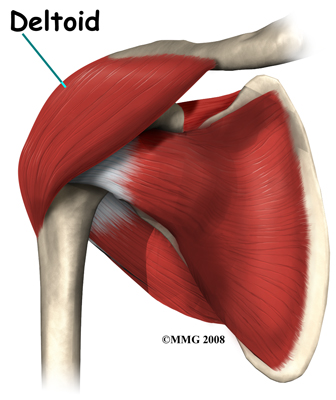

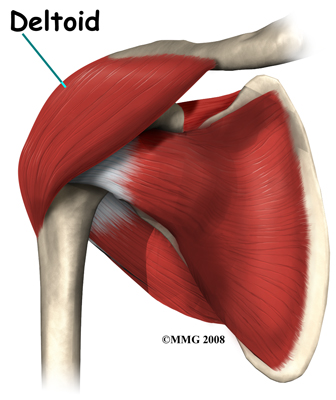

The large deltoid muscle is the outer layer of shoulder muscle. The deltoid is the largest, strongest muscle of the shoulder. The function of the deltoid muscle is to lift the arm further up once the arm is already away from the side of your body.

Related Document: Combined Therapy Specialties Guide to Shoulder Anatomy

Shoulder Anatomy Introduction

Types of Shoulder Dislocations

Anterior Dislocation

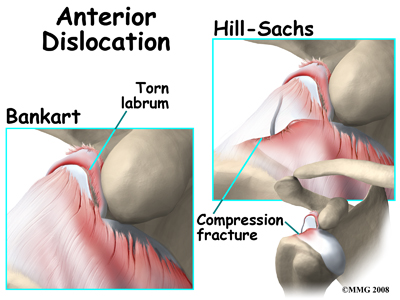

With an anterior dislocation, the head of the humerus is driven forward from inside the glenoid cavity to a place under the coracoid process. This type of dislocation is sometimes referred to as a subcoracoid dislocation. The joint capsule is usually avulsed (torn away) from the margin of the glenoid cavity.

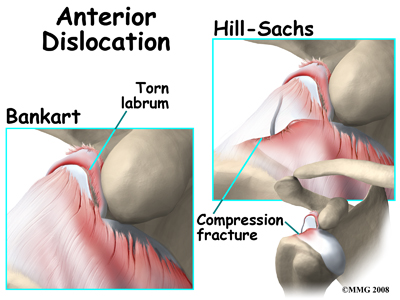

Anterior shoulder dislocation can also be the result of a detached labrum. When both the labrum and the capsule along the anterior margin of the glenoid cavity are avulsed, the injury is called a Bankart lesion. A compression fracture of the humeral head from the force of hitting the hard glenoid during dislocation is called a Hill-Sach's lesion. Seventy-five percent of patients with a Bankart lesion will also have a Hill-Sach's lesion.

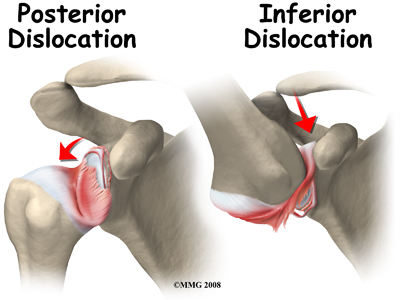

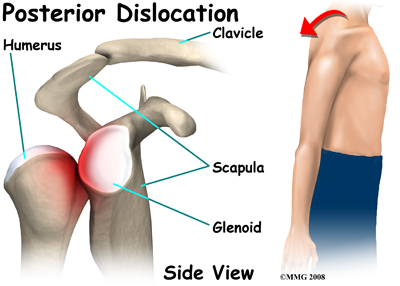

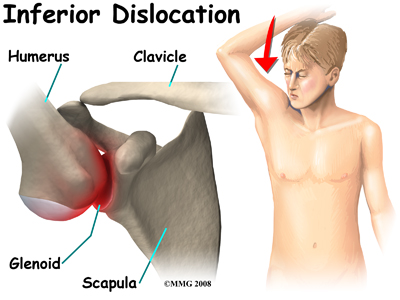

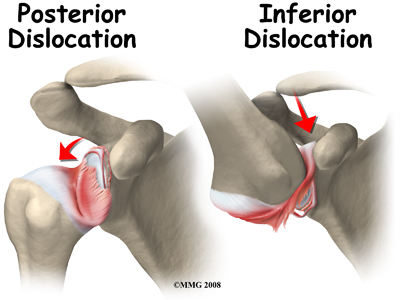

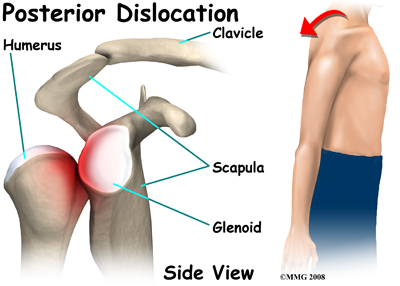

Posterior and Inferior Dislocations

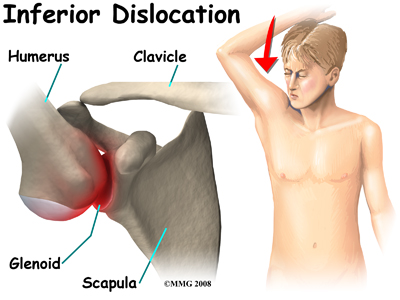

When the shoulder dislocates posteriorly, the head of the humerus moves backward behind the glenoid. An inferior dislocation describes the position of the humeral head down below the glenoid cavity. Posterior and inferior shoulder dislocations only account for about five to 10 per cent of all shoulder dislocations. Most shoulder dislocations are in the anterior direction.

Causes

What causes this problem?

The shoulder is a very mobile joint and therefore more vulnerable to dislocation than some other joints. The glenoid cavity is small in relation to the head of the humerus. Muscles, ligaments, and the bony anatomy of the shoulder all work together to maintain shoulder stability and prevent dislocation. Dislocation can occur when any of these structures are injured or altered in any way or when there is a force great enough to overcome the ability of these structures to hold the shoulder in place.

Forceful abduction (taking the arm out to the side,) external rotation (rotating outwards,) and extension are the most common combined loads that result in a shoulder dislocation. The joint capsule may be lifted off the bone and the head of the humerus gets lodged between the capsule and the bone. A fall on an outstretched hand or directly on the posterolateral aspect (back and side) of the shoulder can cause an anterior dislocation. Violent uncoordinated muscle contractions during a grand mal seizure can also cause shoulder dislocations.

In addition to traumatic causes of shoulder dislocations, non-traumatic factors that alter the structure of the shoulder can predispose the joint to a dislocation. This occurs with repetitive activities that create an imbalance in the strength of the muscles controlling the shoulder, or activities that cause gradual laxity in the ligaments that support the shoulder. For example, patients who have developed very forward rounded shoulders may be at greater risk of dislocaiton as the forward rounded position can cause the ligaments at the front of the shoulder to become lax over time, providing less support to the shoulder joint. A similar situation can arise due to muscle imbalances. Weight lifters who over train their chest muscles (pectorals) in comparison to their back muscles will often cause prolonged stress on the anterior structures of the shoulder which again can lead to laxity in the shoulder supports.

Many athletes whose sports involve repetitive and powerful over-head actions, such as swimmers, volleyball players, and baseball pitchers develop laxity in their shoulders simply from the repetitive stretching of the shoulder ligaments during their sports. Once lax, these ligaments do not provide the necessary passive stability that the shoulder joint needs to remain in its socket, and the joint becomes predisposed to dislocation, especially during the overhead and lateral (wind-up) movements used in their sport. In these situations, the strength and coordination of the rotator cuff muscles and the muscles controlling the shoulder blade become even more important in order to adequately control the shoulder joint during motion and avoid injury.

Once the shoulder has been dislocated the first time, there is a high probability of a second shoulder dislocation (recurrence) especially in a younger population. The force of the first dislocation dislodging the head of the humerus forward leaves a pocket formed by sagging soft tissues that the humeral head can slip back into. Some people with very lax ligaments can dislocate the shoulder and reduce it (manually put it back in place) over and over on their own. This is referred to as habitual dislocation and should be discouraged.

The highest incidence of recurrence is in young people (under the age of 20 at the time of the injury). Sixty per cent of patients between 20 and 40 years will have a recurrence. Only 10 per cent of patients over 40 years will have another shoulder dislocation. Participation in contact sports activity increases the risk of re-injury. After a second dislocation, frequent recurrence of shoulder dislocation can occur with less and less force, load, or stress.

Symptoms

What does the condition feel like?

Most people with a shoulder dislocation experience sudden, severe pain in the shoulder after a fall, injury, or other traumatic event. It's a natural response to hold and support the arm against the body with the other hand.

Pain and a feeling of extreme apprehension with any movement of the arm are common. If instability remains after the shoulder has been reduced, this type of apprehension can be present with daily activities. You may be constantly aware that if you move the arm in just the right way, it will pop out again.

With an inferior dislocation, it is difficult (and sometimes impossible) to bring the arm down to the side. This is because the head of the humerus is caught under the glenoid cavity.

Diagnosis

How do health care professionals diagnose the problem?

The history and physical examination are probably the most important tools used to diagnose a shoulder dislocation. The history of your injury is especially important. If the shoulder remains out of joint, the diagnosis is usually blatant. If, however, the joint has spontaneously reduced after the injury, the diagnosis of a shoulder dislocation having occurred may be less conspicuous.

The history and physical examination are probably the most important tools used to diagnose a shoulder dislocation. The history of your injury is especially important. If the shoulder remains out of joint, the diagnosis is usually blatant. If, however, the joint has spontaneously reduced after the injury, the diagnosis of a shoulder dislocation having occurred may be less conspicuous.

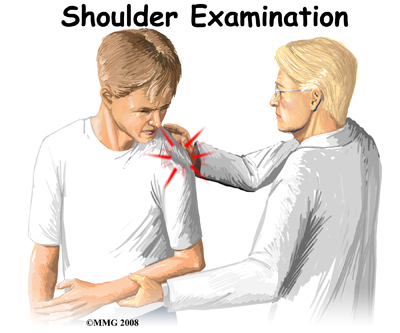

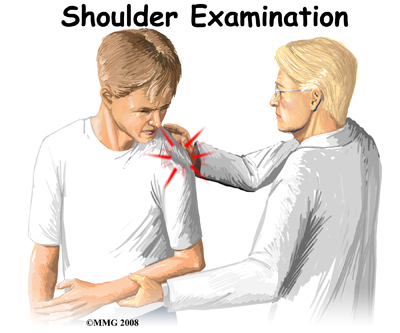

Your physical therapist at Combined Therapy Specialties will ask questions about when and how the injury occurred, where precisely the pain is, how ‘unstable’ the shoulder feels, and which movements are restricted. It will also be important to know whether your shoulder has dislocated in the past or whether you have had previous injuries to either shoulder.

Next your physical therapist will visually inspect the shoulder. When there is a shoulder dislocation that remains out of place, the normal rounded contour of the shoulder and upper arm is lost. Instead, the outside edge of the shoulder looks flat or square. There are changes in the appearance of the surface anatomy. For example, instead of the greater tuberosity (bony bump along top of shoulder) protruding at the side there is a gap under the acromion. The head of the humerus may be observed and felt as a large bump in front or behind the shoulder. The area is usually extremely tender to palpation.

Range of motion, strength, and sensation will be tested if possible. Any there are any changes or loss of sensation this may point to nerve damage that has occurred as a result of the dislocation. Your physical therapist may also check the pulses in your arm in order to detect the possibility of vascular complications.

Range of motion, strength, and sensation will be tested if possible. Any there are any changes or loss of sensation this may point to nerve damage that has occurred as a result of the dislocation. Your physical therapist may also check the pulses in your arm in order to detect the possibility of vascular complications.

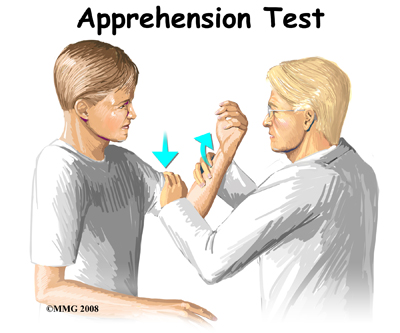

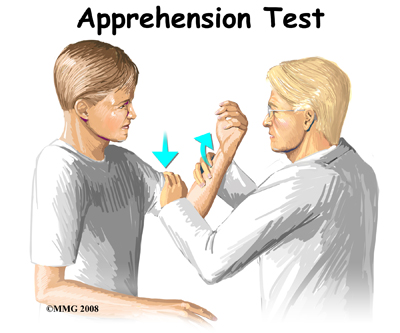

There are many clinical tests that can be performed to identify which soft tissue structures have been damaged or ruptured. A positive apprehension test is very diagnostic of an unstable shoulder that might dislocate anteriorly again after a first dislocation injury. For this test the arm is abducted and externally (outwardly) rotated by your physical therapist. Just prior to the position where the joint is about to dislocate, you may become anxious as the feeling of a potential dislocation occurs. At that point, the test is considered positive for shoulder instability and therefore discontinued.

X-rays are an important diagnostic tool to show the displaced head of the humerus and any bone fractures that may have occurred. Several views may be needed to reveal the exact direction of the dislocation and fracture lines when present. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to diagnose and define the extent of the lesion. MRIs are very accurate in detecting Hill-Sach's lesions, which are explained above.

Combined Therapy Specialties provides services for physical therapy in Asheville.

Treatment / Rehabilitation

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

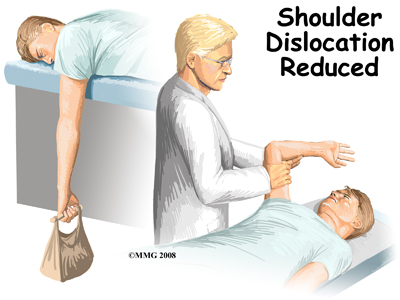

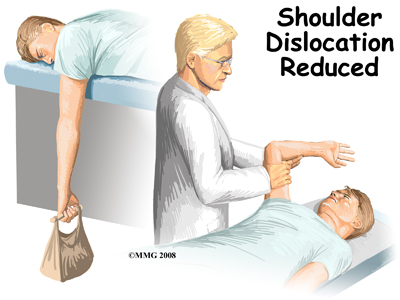

In many cases, the shoulder can be reduced without surgery. This is called a closed reduction. Many health care professionals (especially those trained in emergency procedures) know how to manipulate the shoulder back into the socket. However, without the aid of a general anesthetic, this maneuver can be very painful.

One simple technique used by health care professionals to reduce an anterior shoulder dislocation is done in the prone (face down) position. The injured arm is supported at the edge of the table. The arm is allowed to dangle over the edge of the table with a weight attached. As the shoulder muscles relax, the humeral head passively (on its own) slips back to its normal position. Unfortunately this may take several minutes.

One simple technique used by health care professionals to reduce an anterior shoulder dislocation is done in the prone (face down) position. The injured arm is supported at the edge of the table. The arm is allowed to dangle over the edge of the table with a weight attached. As the shoulder muscles relax, the humeral head passively (on its own) slips back to its normal position. Unfortunately this may take several minutes.

If passive positioning doesn't work for an anterior dislocation, then a general anesthetic is administered and traction is applied to the upper limb. The arm is held in a position of shoulder abduction while lateral (sideways) and backward pressure is applied to the head of the humerus. Posterior shoulder dislocation can be treated in a similar fashion. Under anesthesia, the shoulder is rotated outwardly and forward pressure is applied on the dislocated humeral head.

Some patients who have recurrent dislocations know how to pop their own joint back into place without help. When performed by a health care professional, the procedure is generally done in a timely manner in order to prevent further pain or soft tissue damage.

Functional outcome is also better if the dislocation is reduced early.

Following closed reduction, X-rays are used to confirm correct placement of the humeral head in the glenoid cavity. After reduction, immobilization of the arm in a sling against the chest is usually recommended for several weeks up to a month. This period of immobilization gives the soft tissues a chance to heal.

Following closed reduction, X-rays are used to confirm correct placement of the humeral head in the glenoid cavity. After reduction, immobilization of the arm in a sling against the chest is usually recommended for several weeks up to a month. This period of immobilization gives the soft tissues a chance to heal.

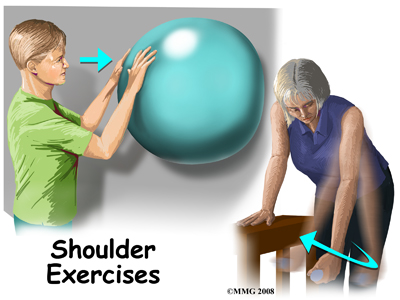

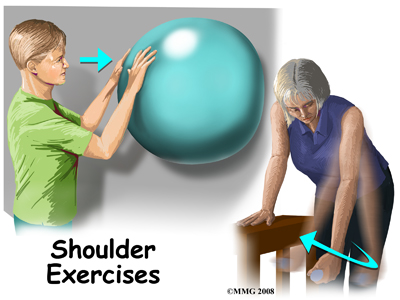

As older adults are more at risk of developing a stiff or frozen shoulder, gentle range of motion exercises called Codman's or pendulum exercises may be prescribed for these individuals. These are usually done once or twice a day with the sling removed.

Recurrent dislocation is the most common complication after dislocation, especially in young people. Older adults are more likely to experience chronic pain and stiffness. When conservative care is unable to restore shoulder stability and normal function, then surgical intervention may be needed.

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

All shoulder dislocations do not require surgery. Many dislocations, especially in middle or older age, can be treated non-surgically. Physical therapy at Combined Therapy Specialties will assist you in restoring the normal function of your shoulder. Immediately following your dislocation, your shoulder will likely require a period of immobilization in a sling for 2-4 weeks. This immobilization is to assist in pain relief, and allow the soft tissue to heal. As mentioned above, in the middle age to older population, a shorter immobilization period avoids a potentially stiff shoulder, whereas in a younger population, the longer immobilization period allows scarring of the tissues to prevent a recurrence of the injury.

Initially, the treatment we provide at Combined Therapy Specialties will be focused on relieving any pain and inflammation caused by the dislocation and reduction of your shoulder joint. We may use modalities such as ice, heat, ultrasound, or electrical current to assist with decreasing any pain or swelling you have. Due to some of the muscles of the neck and upper back connecting to the shoulder, you may also have pain in these regions and require treatment for these areas. Massage may be used for the neck, upper back, and non-painful areas of the shoulder to decrease pain. In addition, taping the shoulder during the initial stages of recovery may assist with pain relief by easing the tension placed on inflamed structures.

While you are immobilized simple finger movements, elbow and neck range of motion exercises should be performed. If your physical therapist or doctor has stated that your shoulder is at risk of becoming stiff, pendular (Codman) exercises (with the immobilizer removed), will also be encouraged. Pendular exercises assist with pain relief, help to maintain some shoulder range of motion, and assist in preventing unwanted scar tissue forming in the joint. These exercises are performed by leaning forward or to the side, letting the arm hang clear of the chest, and then initiating movement with your trunk so that the dangling limb passively and gently moves. This action provides some traction to the glenohumeral joint, which aids in pain relief, and also assists the shoulder into a relative elevated motion (in relation to the trunk.) It is important that the pendular activity is done as passively as possible without initiating motion from the shoulder muscles. The exercise should be similar to a weighted pendulum that randomly swings on the end of a piece of string.

At Combined Therapy Specialties we highly recommend maintaining the rest of your body’s fitness with regular exercise even while your shoulder is immobilized. Cardiovascular fitness can be maintained with lower extremity fitness activities such as walking or using a stationary bike or stepper machine. None of these exercises should cause discomfort to your shoulder; if this occurs, discuss modifying the activity with your physical therapist.

The next part of our treatment will focus on regaining the range of motion, strength, and coordination in your shoulder. The desired outcome of rehabilitation after shoulder dislocation is a return to full function. For athletes, this means full participation in sports activities. Depending on how long you were immobilized, your age, as well as the severity of the injury, your arm may feel very weak and be limited in its range of motion once the immobilizer is removed. Shoulders that have not lost some range of movement after the period of immobilization are often suspicious for eventual recurrence of the dislocation.

In order to gain back your range of motion, strength, and function of your shoulder your physical therapist at Combined Therapy Specialties will prescribe a series of stretching and strengthening exercises that you will practice in the clinic and also learn to do as part of a home exercise program. These exercises may include the use of rehabilitation equipment such as pulleys and poles for range of motion exercises, and light weights or Theraband for resistance work of your upper limb. As mentioned previously, the shoulder joint is very mobile, but anatomically not very stable and relies heavily on the strength and coordinated function of the muscles around it to maintain its stability and avoid dislocation. The rotator cuff muscles that assist to hold the shoulder joint in the socket are particularly important so will be targeted with rotational resistance activities of the shoulder in different ranges of motion. Adequate strength and endurance in the rotator cuff muscles throughout a variety of ranges of motion is needed to ensure full functioning of the shoulder. An upper body bike may be useful in the early stages of rehabilitation to improve range of motion and encourage coordinated movement of the entire upper limb.

If necessary, your physical therapist will mobilize your shoulder joint. This hands-on technique encourages your shoulder to move gradually into its normal range of motion. Fortunately, gaining range of motion and strength once the shoulder is no longer immobilized occurs fairly quickly. You will notice improvements in the functioning of your shoulder even after just a few treatments with your physical therapist at Combined Therapy Specialties.

As a result of any injury, the receptors in your joints and ligaments that assist with proprioception (the ability to know where your body is without looking at it) decline in function. This is particularly true when the stability of a joint has been disrupted. A period of immobility will add to the decline of these receptors. Although your arm and shoulder girdle are not traditionally thought of as weight-bearing parts of the body, an activity such as assisting yourself with your arms to get out of a chair, pulling a glass from a cupboard, or even shaving requires weight to be put through or lifted by your shoulder girdle and for your body to be proprioceptively aware of your limb. If you are an athlete, then proprioception of your upper extremity is paramount in returning you to your sport after a shoulder dislocation. Overhead sports such as swimming, or volleyball require even more precise control of the shoulder joint and girdle in order to fully return to your sport.

Controlled scapulothoracic motion is particularly essential when using your limb near or above shoulder height and especially during rapid arm movements such as throwing. By ensuring proprioceptive control of the scapula on the rib cage (scapulothoracic motion) you decrease the risk of further injury to the shoulder and the risk of another dislocation. For this reason, your physical therapist will teach you how to properly control your scapula during your rehabilitation exercises but will also educate you on transferring this control to your everyday activities. As you improve with being able to control the shoulder girdle your physical therapist will introduce more difficult dynamic exercises for your shoulder including exercises that simulate your everyday activities, or if you are an athlete, those shoulder motions that simulate your sport. Simple proprioceptive exercises might include activities such as rolling a ball on a surface with your hand, holding a weight up overhead while moving your shoulder, or pushups on an unstable surface. Advanced exercises may include activities such as reaching and lowering a weight, ball throwing, catching overhead, or a simulated swimming stroke or overhead spike. Your physical therapist will tailor your proprioception exercises to best address your direction of instability, your level of ability, and your return to function goal.

No matter which direction your shoulder has dislocated gaining scapulothoracic and glenohumeral control particularly during dynamic overhead motions and weight bearing activities is paramount in returning you to your full activities. If these advanced exercises cannot be mastered without pain or a feeling of apprehension, it is often reason for a surgical intervention to be considered and your physical therapist will liaise with your surgeon if this is the case. Unfortunately, regaining proprioception of the shoulder girdle and upper limb requires concentrated and determined work, and most people have not previously needed to focus so intently on such controlled motions of their shoulder blade and arm. The concentrated effort, however, has a substantial reward, as good scapulothoracic control is the key to regaining maximum shoulder function after a dislocation, preventing a second dislocation, and avoiding secondary pain from shoulder impingement in the future. Whether treating a shoulder dislocation non-surgically or surgically, scapulothoracic control is an essential part of your physical therapy rehabilitation.

Finally, as part of your shoulder rehabilitation, your physical therapist will also remind you about maintaining good shoulder posture at all times even when just sitting or using your upper limb in activities below shoulder height, such as working on the computer. Rounded shoulders in any position crowds the shoulder joint and can lead to shoulder impingement and pain as you recover from your dislocation.

Rehabilitation after a shoulder dislocation responds very well to the physical therapy we provide at Combined Therapy Specialties. As a general guide you can return to you will be able to return to your full sporting activities as long as there is no pain or recurrent swelling, when your muscles are back to nearly their full strength and control, and you aren't having problems with the shoulder popping out of the joint.

Combined Therapy Specialties provides services for physical therapy in Asheville.

Surgery

Surgery for the dislocated shoulder may be required if the shoulder can't be reduced manually or non-surgical treatment, as outlined above, does not control the symptoms of instability during every day or sporting activities. The main goal of surgery is to reduce and/or stabilize the shoulder. Restoring normal motion and function as well as preventing recurrent dislocations are important long-term goals of surgical intervention.

Even when surgery is deemed to be the first intervention for stabilization, your surgeon may have you see a physical therapist for several visits before the surgery. This is done to reduce swelling, strengthen the muscles, and conservatively work to stabilize the shoulder as much as possible before surgery. This practice also reduces the chances of scarring inside the joint and can speed recovery after surgery.

There are many different ways to repair a chronically unstable shoulder following a first dislocation or after many recurrent shoulder dislocations. The direction of instability (anterior, posterior, inferior, or some combination) is taken into consideration when choosing the best reconstructive technique. The site, type, and extent of damage, as well as the return to activity goal are also major determining factors in how the surgeon approaches the repair.

Shoulder reconstruction surgery may be done with an open incision method or arthroscopically. The arthroscope is a small camera used to view the inside of the shoulder joint as the surgeon performs the work. Other small incisions are made for the instruments to be inserted into but it is not necessary to open up the joint completely. For this reason, the surgical scars you will see are significantly smaller. Your surgeon will decide which technique to use based on the repair needed, risk for infection, surgical preference, and other factors. Some procedures cannot be adequately fixed with arthoscopic surgery so an open repair is optimal.

One of the most common procedures used in repairing the shoulder after an anterior dislocation is the Bankart operation, which aims to repair the Bankart lesion explained above. During the Bankart reconstruction procedure, the labrum and capsule are reattached to the anterior margin of the glenoid cavity in order to try and restore the normal anatomy and stability of the shoulder.

Older adults who have a fracture and shoulder dislocation may need a shoulder replacement instead of a shoulder reconstruction surgery to reduce the dislocation and repair the fracture.

After Surgery

Many shoulder reconstructive surgeries are now done on an outpatient basis. Patients go home the same day as the surgery. Some patients stay one or two nights in the hospital if necessary.

After any surgery to stabilize the shoulder your shoulder will be immobilized. You will probably wear a sling or hard brace for three to six weeks. Your surgeon will decide on the optimal amount of time for immobilization after your surgery based on the surgical procedure performed, your individual anatomy, your rehabilitation goals, and the surgeon’s personal experience. A large abduction wedge under the armpit holds the arm in just the right position. The soft tissues must be given enough time to heal and form scar tissue to support and stabilize the shoulder joint.

Some studies are being done to investigate the use of early motion (within two to three days) after the operation, which obviously has the benefit of an early return to activity and, in addition, tends to decrease the amount of postoperative pain that occurs. All surgeons have not adopted this accelerated rehabilitation protocol routinely as it is also argued that the early motion can allow the scar tissue to stretch more which in turn allows the joint to become too loose. Functional recovery without immobilization or with minimal immobilization nonetheless has been proven possible. Athletes may be most likely to try this accelerated rehabilitation in order to return to sports participation as soon as possible.

Post-surgical Rehabilitation

Once the immobilizer has been removed, formal physical therapy will begin. While you are immobilized simple finger movements, elbow and neck range of motion exercises will be your only exercise. Some surgeons may recommend or allow early pendular exercises with the immobilizer removed (as explained above) to assist with pain relief. Some may also encourage a few simple shoulder range of motion exercises within the limits of pain almost immediately. Generally each surgeon has a specific rehabilitation protocol that is used after their shoulder stabilization surgery, and your physical therapist at Combined Therapy Specialties will liaise with your surgeon to ensure the progression of exercises is appropriate for your individual case.

Rehabilitation following shoulder stabilization surgery will follow a similar pattern to the rehabilitation described above under non-surgical treatment. Stiffness and pain, however, are often a more significant issue following surgical versus non-surgical treatment due to the surgery itself and the more prolonged immobilization. For this reason, modalities such as ice, heat, ultrasound, or electrical current may be more regularly used and physical therapy treatments at Combined Therapy Specialties will be more regular especially in the first few weeks after beginning treatment. It should be remembered that the goal of surgical intervention following a shoulder dislocation is to make the shoulder stable. It is thus expected and natural that the shoulder is quite stiff on the initial removal of the immobilizer. This stiffness will gradually decrease with the exercises and treatment performed by your physical therapist at Combined Therapy Specialties. If your shoulder does not gain range of motion as we would expect, and remains very stiff, we will liaise with your surgeon immediately. Overall you should expect overall functional rehabilitation after your stabilization surgery to last 3-6 months once it has begun.

After the first stage of treatment, when pain becomes less of an issue and range of motion nears full, you will start to do more functional exercises. This is usually around the 3-6 week mark after beginning rehabilitation at Combined Therapy Specialties. During this time, your physical therapist will work with you to gain the final degrees of motion, as well as increase your strength, and control as outlined above under non-surgical rehabilitation.

For another 6-12 weeks after this time frame, when your shoulder is further into a late recovery stage, the exercises will become more advanced. These exercises are designed to gain muscle endurance and challenge your scapulothoracic motion and control. The need for an adequately controlled shoulder girdle will become apparent as you begin to return to all your activities of daily living. During this time, less regular treatments at Combined Therapy Specialties will be necessary, but you will be required to intensely continue your home program.

For athletes, the full-to-sport phase begins about three to four months after surgery. Your physical therapist at Combined Therapy Specialties will put you through a series of sport-specific drills designed to improve your coordination, speed, and agility. In order to participate in this level of rehab, you must have the normal range of motion and flexibility needed for your sport or activity, and 90 per cent of normal strength. You must also be free of symptoms during activities or sport-specific drills.

Rehabilitation post shoulder stabilization surgery generally responds very well to the physical therapy we provide at Combined Therapy Specialties and patients can return to their normal activity. If, however, during rehabilitation your pain continues longer than it should or therapy is not progressing as your physical therapist would expect, we will ask you to follow-up with your surgeon or doctor to confirm that the shoulder is tolerating the rehabilitation well and to ensure that there are no hardware issues that may be impeding your recovery.

Portions of this document copyright MMG, LLC.

Welcome to Combined Therapy Specialties resource about shoulder dislocations.

Welcome to Combined Therapy Specialties resource about shoulder dislocations.

The shoulder has a unique and complex anatomy that allows range of motion and coordination needed for reaching, lifting, throwing, and many other movements. Understanding the anatomical structures discussed will help you understand why your shoulder dislocated.

The shoulder has a unique and complex anatomy that allows range of motion and coordination needed for reaching, lifting, throwing, and many other movements. Understanding the anatomical structures discussed will help you understand why your shoulder dislocated.

There are several important ligaments in the shoulder. Ligaments are soft tissue structures that connect bones to bones. A joint capsule is a watertight sac that surrounds a joint. In the shoulder, the joint capsule is formed by a group of ligaments that connect the humerus to the glenoid. These ligaments are the main source of stability for the shoulder; they help hold the shoulder in place and keep it from dislocating.

There are several important ligaments in the shoulder. Ligaments are soft tissue structures that connect bones to bones. A joint capsule is a watertight sac that surrounds a joint. In the shoulder, the joint capsule is formed by a group of ligaments that connect the humerus to the glenoid. These ligaments are the main source of stability for the shoulder; they help hold the shoulder in place and keep it from dislocating.

The tendons of the rotator cuff are the next layer in the shoulder joint. Four rotator cuff tendons connect the deepest layer of muscles to the humerus. This group of muscles attaches from the shoulder blade to the humerus. These muscles help raise the arm from the side and rotate the shoulder in the many directions. They are extremely important muscles to the shoulder and are involved in many day-to-day activities. The rotator cuff muscles and tendons are extremely important in assisting glenohumeral joint stability because they help hold the humeral head in the shallow glenoid socket.

The tendons of the rotator cuff are the next layer in the shoulder joint. Four rotator cuff tendons connect the deepest layer of muscles to the humerus. This group of muscles attaches from the shoulder blade to the humerus. These muscles help raise the arm from the side and rotate the shoulder in the many directions. They are extremely important muscles to the shoulder and are involved in many day-to-day activities. The rotator cuff muscles and tendons are extremely important in assisting glenohumeral joint stability because they help hold the humeral head in the shallow glenoid socket.

The history and physical examination are probably the most important tools used to diagnose a shoulder dislocation. The history of your injury is especially important. If the shoulder remains out of joint, the diagnosis is usually blatant. If, however, the joint has spontaneously reduced after the injury, the diagnosis of a shoulder dislocation having occurred may be less conspicuous.

The history and physical examination are probably the most important tools used to diagnose a shoulder dislocation. The history of your injury is especially important. If the shoulder remains out of joint, the diagnosis is usually blatant. If, however, the joint has spontaneously reduced after the injury, the diagnosis of a shoulder dislocation having occurred may be less conspicuous.  Range of motion, strength, and sensation will be tested if possible. Any there are any changes or loss of sensation this may point to nerve damage that has occurred as a result of the dislocation. Your physical therapist may also check the pulses in your arm in order to detect the possibility of vascular complications.

Range of motion, strength, and sensation will be tested if possible. Any there are any changes or loss of sensation this may point to nerve damage that has occurred as a result of the dislocation. Your physical therapist may also check the pulses in your arm in order to detect the possibility of vascular complications. One simple technique used by health care professionals to reduce an anterior shoulder dislocation is done in the prone (face down) position. The injured arm is supported at the edge of the table. The arm is allowed to dangle over the edge of the table with a weight attached. As the shoulder muscles relax, the humeral head passively (on its own) slips back to its normal position. Unfortunately this may take several minutes.

One simple technique used by health care professionals to reduce an anterior shoulder dislocation is done in the prone (face down) position. The injured arm is supported at the edge of the table. The arm is allowed to dangle over the edge of the table with a weight attached. As the shoulder muscles relax, the humeral head passively (on its own) slips back to its normal position. Unfortunately this may take several minutes. Following closed reduction, X-rays are used to confirm correct placement of the humeral head in the glenoid cavity. After reduction, immobilization of the arm in a sling against the chest is usually recommended for several weeks up to a month. This period of immobilization gives the soft tissues a chance to heal.

Following closed reduction, X-rays are used to confirm correct placement of the humeral head in the glenoid cavity. After reduction, immobilization of the arm in a sling against the chest is usually recommended for several weeks up to a month. This period of immobilization gives the soft tissues a chance to heal.